DTC's Response to SEC RFI for Information on Investment Adviser Use of Technology to Develop and Provide Investment Advice

From: Eric S. Smith, J.D., Chairman & CEO, Decision Technologies Corporation (“DTC”)

To: The Securities & Exchange Commission (“SEC”) via rule-comments@sec.gov File No. S7- 10-21 // cc: Division of Trading and Markets, Office of Chief Counsel, via tradingandmarkets@sec.gov and Division of Investment Management, Investment Adviser Regulation Office via IArules@sec.gov.

Date: October 1, 2021

Re: Information regarding a newly available decision-assistance technology, introduced and described at ProRRT.com, that enables investment advisors to score and rank investment choices in a manner specific to the needs, goals, and propreferences of individual investors, optimizing investment selection recommendations in such a way as to ensure that such recommendations are provably in the best interests of individual investor clients and that conflicts of interest, both known and unknowable, are effectively filtered out.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

Ongoing federal and state regulatory efforts toward ensuring that what is being recommended and sold by securities brokers and investment advisors is in their customers’ and clients’ “best interests” continue to face industry push-back. The principal arguments against such efforts have been that:

- there is no way to determine what is “best” for any client; there are too many choices and too much information about them; and securities brokers / FINRA additionally argue that

- requiring FINRA-registered securities brokers to effectively become “fiduciary” advisors will prevent small investors from being served – that unless “suitable” products (as defined by FINRA) can simply be sold to them, it will not be economically feasible for securities brokerage firms to serve small investors at all.

A newly available decision-assistance technology appears to effectively address these objections and provides a way for brokers and advisors to comparatively evaluate thousands of investment choices in a manner specific to individual clients’ needs, goals, and preferences. Moreover, it does so objectively, transparently, and in a way that effectively filters out all conflicts of interest, both known and unknowable.

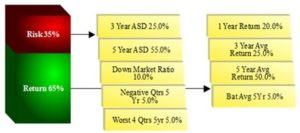

The technology enables investment professionals to pick any number of performance parameters (from 48 possible choices – more are being added), which can then be hierarchically arranged and weighted to profile the ideal “investment effect” desired. Utilizing that composite blend of weighted factors, the available investment choices, within any relevant asset class, can be scored and ranked. The resulting ranked list shows how the client’s investment selections objectively compare with those mutual funds and ETFs that have proven best over time at producing the desired composite performance, within the relevant asset class.

This newly available technology is now being offered to professional investment advisors and securities brokers at ProRRT.com, where detailed information about it can be reviewed.

The technology was developed with one key goal in mind – to help answer this important question: “Of all the available choices, which ones are best for my clients?”

There’s now an objective and transparent way to answer that question and provably demonstrate that what is being recommended and sold to customers / clients is in their best interests. The ability to answer that question may now help to determine what is regulatorily possible and reasonable.

DISCUSSION:

THE INVESTOR PROTECTION “PROBLEM” AND SOME UNDERLYING CAUSES.

In the continuing struggle to ensure that investors are protected from the adverse effects of:

- Pervasive conflicts of interest;

- Deceptive, manipulative, and/or predatory practices; and the

- Growing number of investment choices and overwhelming amounts of information about them,

these listed issues all appear to coalesce in one simple question: “Of all the available choices, which ones are best for the client?” Strangely, there appears to be little serious interest in finding a way to for brokers and advisors (much less their clients(1)) to objectively answer that question. Why?

The debate surrounding the promulgation of the Department of Labor’s ill-fated “fiduciary rule” and the SEC’s creation of its Reg. BI, is enlightening. Both regulatory efforts faced strong pushback from the financial services industry, especially from securities brokers and FINRA.(2) Pointing to the bewildering and growing number of investment choices, they effectively argued that it is not possible to determine what is “best” for any client, and regulations should not require the impossible.

To date, that argument appears to have been both successful and virtually impossible to refute. Yet, in this “information age,” is it reasonable to believe that it has not been possible for a $90+ trillion financial services industry to develop a way to manage all of that data? Is it truly impossible to find a way to ensure that what advisors and brokers are recommending and selling to their clients is provably in their best interests? Or is there little to no interest in doing so? Would doing so simply be too disruptive of the way the financial services business has always been conducted? Unfortunately, the answers to the last two questions might well be “yes,” and one reason immediately seems obvious.

The financial services marketplace is and has been vendor-dominated since its inception. The sale of financial products is the motivating force driving it. Moreover, competition among its vendors typically involves pricing and compensation “incentives” designed to ensure the preferential recommendation and sale of one vendor’s products over those of other vendors. Until the SEC’s recent action compelling disclosure of these arrangements, these conflicts of interest were seldom voluntarily disclosed, for obvious reasons – nothing about those arrangements is good for investors.

IS REQUIRING THE DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST THE “SOLUTION?”

We submit that the answer, unfortunately, is “NO” – that is, if the goal is to try to ensure that what is being recommended and sold to customers / clients is in their best interests. The reason is that requiring even the full disclosure of conflicts of interest will not alone be sufficient to structurally change the way the financial services marketplace works. That marketplace will still be vendor- dominated and still likely incentive-driven. One can simply perform the following though experiment to understand the concern:

- Imagine that brokerage and investment advisory firms all scrupulously comply and begin to disclose that each, in some form or fashion, receives incentive compensation or are in other ways benefited from vendor relationships in ways that can potentially affect their investment recommendations and the universes of investment choices from which they recommend and sell. If all or virtually all disclose such conflicts, with no ready way for customers / clients to identify and move to others with no such conflicts (assuming they exist), has anything truly protective of investors really been accomplished? Or will such disclosures become “just one more ‘form’” that the broker or advisor must present and get signed by their customer / client? Will the customer / client simply believe (or perhaps be led or encouraged to believe) that such disclosures are going to be pretty much the same wherever they go and so conclude that it’s likely to be futile to inquire further . . . better to just go ahead and sign it and move on?

We submit that it is unlikely that requiring even complete conflict of interest disclosures will alone be sufficient to produce meaningful structural changes in the way the financial services industry works, nor is it likely to be sufficient to ensure a significantly more effective level of investor protection. We believe the key to achieving a desired greater level of investor protection will require a way to effectively address the large and growing number of financial products and the bewildering array of information about them. In other words, we believe the key will lie in overcoming the arguments relied upon by the financial services industry in its resistance to rules designed to ensure that what is being recommended and sold to clients is in their clients’ best interests.

Effectively addressing the overwhelmingly large and growing number of financial products and information about them is the key. It is estimated that there are now over 30,000 mutual funds and share classes and as many as 5,000 – 6,000 separate account managers in the U.S. alone. With so many choices and so much information available about them, there has been no practical way for even “experts” to be knowledgeable about, much less be able to comparatively evaluate, all of them.

Consequently, many brokerage and advisory firms simply select relatively small “approved” subsets of investment choices from which they recommend and sell. They often justify this by arguing that there is no practical way to do due diligence on so many choices. But exactly how these relatively small, proprietary universes are created is seldom disclosed. What it takes be included / to “get in” is not generally available and not verifiable by customers or clients, or even their advisors, and this too often proves to be where those wanting “in” must “pay to play.” Ultimately, a major part of the problem arises from competition among thousands of vendors, in which those with dominant market positions and much greater resources can secure competitive advantages through incentivized distribution arrangements against which smaller vendors with less resources cannot effectively compete.

Having too much information, with no practical way to use and benefit from it, is the functional equivalent of having no information at all. This has long worked to the advantage of the financial services industry.(3) Having too many choices and too much information about them, with no practical way to comparatively evaluate them, has effectively required investors at all levels (both individual and institutional) to be almost entirely dependent upon the investment recommendations of securities brokers and investment advisors.(4) As discussed above, this has also served as a justification of the financial services industry’s push-back against regulations focused on ensuring that what is recommended and sold to investors must be in the investors’ “best interests.”

The patented decision-assistance technology now being introduced fundamentally changes this. Because it is often difficult to envision what one has never experienced, seeing the technology demonstrated is indispensable in understanding its potential benefits and likely effects. We look forward to providing such demonstrations for those of the SEC’s staff reviewing this submission.

THE SEARCH FOR AN ANSWER / A WAY TO BETTER PROTECT INVESTORS.

For us, the key question – “Of all the available choices, which one is best?” – lingered, unanswered for years and ultimately resulted in an important realization – that to answer that question, three things would be needed:

- Universal market access to all available choices, something most believed impossible to secure;

- No compromising relationships with vendors of financial products and services, the accomplishment of which appeared to be simply a matter of corporate “Will”; and,

- A “Process” that could accomplish 3 things, also generally thought impossible to achieve:

- The ability to cut through all of the “noise” in the markets from the plethora of advertising and marketing materials;

- The ability to filter out all conflicts of interest, both known and unknowable; and, the

- Ability to use the vast amounts of obtainable information to comparatively evaluate all available investment choices in a manner specific to the needs, goals, and preferences of advisors and investors.

The last of the three led to the creation the patented decision-assistance technology that enables users, whether investment advisors, brokers, and (ultimately) individual investors, to comparatively evaluate literally thousands of mutual funds, ETFs, money managers and (prospectively) annuities and other financial products in a manner specific to their individual needs, goals, and preferences. The technology optimizes and objectifies investment selection in a way previously unavailable(5) to securities brokers and investment advisors and, in doing so, provides a way to definitively answer the key question posed above.

As illustrated below, the technology works by enabling users to select any number of performance parameters, which can then be hierarchically arranged and weighted, to profile the “composite investment effect” ideally desired from any asset class comprising an investor’s portfolio. The technology then enables the user to score and rank thousands of choices and to identify which of the mutual funds, ETFs, or money managers have been the best at producing the desired composite investment effect over time.

When users are not only able to see but also control the selection of, and degree of emphasis placed on, the factors important to them, transparency is assured. And, if an investor client can not only see but can also directly participate in how his or her investment advisor is comparatively evaluating choices within the universes from which the

client must choose (e.g., helping to select and weight the performance factors being used), there is no way to “game” the process, meaning actual and potential conflicts of interest are filtered out. We believe that, in this way, the goal of true investor protection could possibly be realized.

But there is another important dimension to the application of this decision-assistance technology. Much like the key question posed above regarding investment selection, we submit that there is another key question – one regarding ongoing performance monitoring and investment retention and replacement decisions. That additional question is not: “How did our mutual funds, ETFs, and/or investment managers do?” Investors get that question answered. They’re shown how much their investment choices went up or down and that is then typically compared to a “benchmark index.”

That’s typically all that’s provided. Instead, we submit that the question virtually all investors would ideally wish to have answered is this: “How did our choices do relative to all of the others we could have selected?” Much like the earlier discussed “key question,” this question appears to have also seldom (if ever) been seriously addressed, and current performance reports (at both the individual and institutional levels) typically do not enable investors to answer either of the above two questions.(6)

There is a significant difference between “absolute performance” (which is currently reported) and “relative performance” (which almost never is) and what has been missing is relative performance information – information that will enable advisors and their investor clients to answer the above two important and common sensical questions. In this “information age,” it is surprising and difficult to understand why, despite chronically poor investment results, there has been no meaningful evolution in investment performance reporting and in the information provided to investors.(7)

THIRD PARTY REVIEWS AND EVALUATIONS.

Included with this submission is an independent evaluation of the application of the decision-assistance technology within the financial services marketplace. It was performed by one of the top “Quants” on Wall Street, C. Michael Carty, former President of the NYC Chapter of QWAFAFEW (www.qwafafew.org). His conclusions are worth special attention.

It is believed that this technology represents an evolutionary step beyond the most sophisticated metrics currently used in investment consulting. Beyond the continuing use of bar charts and scatter charts in institutional investment reports, 30-40 year old “technology” that provides no actionable data, some of the most sophisticated metrics currently in use (e.g., Sharpe Ratios, Sortino Ratios, Information Ratios, etc.) are also quite old and were developed before later advances in computing power. Component parts of these metrics cannot be varied – i.e., factors cannot be added or deleted, and the degree of influence of any factor cannot be increased or decreased.

In contrast, with this newly available technology, any number of performance parameters can be selected, hierarchically arranged and weighted. With that resulting blend of weighted factors, full universes of available choices can be scored and ranked in a manner specific to the unique needs, goals, and preferences of the brokers, advisors and their clients, and this can be done in real time and in mere moments. Importantly, this process produces actionable data. Brokers, advisors, and their clients can see the investment choices that have proven best over time at producing the composite investment effects they are seeking. Attention can then be more efficiently shifted to qualitative due diligence focused on only the top performers.(8)

Additionally, the nationally prominent Wagner Law Group (https://www.wagnerlawgroup.com/) has also rendered a legal Opinion strongly supportive of the use of the decision-assistance technology, especially in helping to meet the requirements of Reg. BI, as well as the requirements of ERISA regarding the investment-related decision making of retirement plan sponsors and trustees. Included with this submission is a copy of that legal Opinion.

Although both evaluations focus principally on the protective, compliance related “RegTech” aspects of the technology, the “WealthTech” benefits should not be overlooked or minimized. As discussed above, use of this technology will likely result in improved performance for the investor. Specifically, performance gaps revealed using the technology, between choices currently in place and qualified alternatives, are often quite dramatic and (while past performance is no guarantee of future results) moving to choices demonstrating better composite performance over time can have a dramatic effect on the financial wellbeing and retirement security of investors. Simply filtering out conflicts of interest, which can too often corrupt investment recommendations and degrade investment results, should almost assuredly help to improve investment results. Any process that can effectively help to improve investment results could have powerfully beneficial and far-reaching effects.(9)

SUMMARY – IS THIS NEWLY AVAILABLE TECHNOLOGY “THE SOLUTION?”

We believe that it may be, if accepted and used.(10) From over a decade-long experience with the application of this newly available technology,(11) we are confident that it provides a unique answer to the industry’s pushback against “best interests” and “fiduciary” rules and regulations, at both the federal and state levels. How much better can one ensure (and provably demonstrate) that what is being offered to an investment customer / client is in that investor’s “best interests” than to score and rank all available choices, using hierarchically arranged and weighted blends of performance factors specifically selected to match that investment customer’s / client’s needs, goals, and preferences, especially when the process, factors, and weightings are transparently visible to the customer / client who can also directly provide their input? Importantly, since the application of this technology can effectively filter out all conflicts of interest (both known and unknowable), it appears to provide a solution that not only achieves conflict of interest-related regulatory goals but appears to go beyond what has likely been believed to be possible. Consequently, we believe this is a technology of which the SEC should be aware and one deserving of consideration.(12)

Endnotes:

(1) For individual investors, the question is nearly identical: “Of all the available choices, which ones are best for me?”

(2) The brokerage community / FINRA also argue that requiring brokers to effectively become “fiduciary” advisors will prevent small investors from being served. Because “advising” clients is more time consuming and necessitates higher total fees than smaller investors can easily afford, they argue that, unless “suitable” products can simply be sold to them, it will not be economically feasible for small investors to be served at all. That appears to assume that small investors are somehow benefited from the ability of the brokerage industry to sell them what securities brokers and FINRA unilaterally determine to be “suitable,” as in “trust me, this is ‘suitable’ for you.” However, increasing regulatory focus on this issue appears to suggest that, in actual practice, this “standard” has not been sufficient to protect the investing public, especially not small investors.

(3) One real, though less obvious, benefit is that it effectively operates to help prevent investment products from becoming “commoditized” – a result feared by financial product vendors. If brokers and advisors could quickly and easily comparatively evaluate financial products, it could effectively “commoditize” them. Large and better-known mutual fund companies especially consider this to be a very serious threat, and something to be prevented.

(4) As perceived “experts,” with greater access to information and superior product knowledge, their recommendations are almost universally accepted and relied upon. Both institutional and individual investors have virtually no meaningful ways to independently “vet” the investment information and recommendations they are given.

For trustees of 401(k), 403(b) and other defined contribution plans, this could soon become a crisis, as the result of a dramatic increase in class-action lawsuits against both the sponsors and trustees of such plans. The defense often offered by plan trustees, that “we relied on the advice of our investment consultant,” cannot be relied upon. A federal court has ruled that relying on the advice of an investment consultant was not a complete defense to a charge of fiduciary imprudence

. . . that, at the very least, the trustees must have some way to ensure that their reliance on the advice of their investment consultant is reasonably justified. See the line of cases, culminating in the unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decision in Tibble v. Edison, 135 S.Ct. 1823, 1825 (2015) – decision in favor of the plaintiffs (the participants in Edison’s 401k plan).

(5 )The granting of a U.S. Patent covering this technology, and advisory process that is supported by it, is prima facie evidence that there was nothing similar available within the U.S. financial services marketplace. When patent applications are filed, a “prior art” search is conducted and, if something similar is found, a patent is not issued because the invention has failed the “uniqueness” test.

(6) Even though the investment reports of institutional investment consultants typically contain a vast of amount of statistical and other data concerning the fund’s investments and investment results, the information they provide is too often not actionable and is seldom sufficient to help prevent pervasive chronic underperformance. Their investors clients can certainly conclude that they are not happy with their performance, but that is all. They typically cannot tell, from their investment reports, which investment choices have been performing better than theirs, much less which have been best at producing the composite investment results that would most closely match their needs, goals, and preferences over time.

(7) Regarding this, one prominent (now retired) CFO of a major city, when shown this newly available decision-assistance technology, stated: “I was around when bar charts and scatter charts were introduced into institutional performance reporting, some 30+ years ago. Since then, I’ve never seen any evolution the way performance reporting has been done, until now. I had almost given up hope of ever seeing any improvement.”

(8 )This is important, because this provides a meaningful counterargument to the industry’s objection (to stronger “best interest” rules) that “there’s no way any company, no matter how large, can do qualitative due diligence on so many choices.” With is process, qualitative due diligence (which will always be necessary) can be focused on only the top 3-5 choices. Why would one perform qualitative due diligence on number 176, for instance, if there is no interest (from a composite performance point of view) in picking that choice? This technology will help produce much greater efficiencies in investment choice selection and ongoing performance monitoring.

(9) For example, chronic underfunding of public pension plans is becoming an existential threat to far too many cities, counties, and states. Rather than a remedy to underfunding, chronically subpar investment performance too often proves to be an aggravating factor, making chronic underfunding worse. Clearly, for such chronically underfunded and underperforming plans, whatever process is being used for active investment manager selection and ongoing performance monitoring has not been working well and hasn’t been for some time.

(10) Whether or not it will be adopted and used, and at what rate, by FINRA-registered brokers and SEC-regulated investment advisors is presently unknown. Securities brokers and investment advisors effectively enjoy a “monopoly:” on information relating to investment choices. As such, we’ve found that some feel that they don’t need this technological capability. Because their clients simply accept their recommendations, some appear to feel that they don’t need to try to determine what’s objectively “best” for their clients. On the other hand, in a financial services marketplace in which everyone appears to be doing the same things in largely the same ways, we believe this technology could offer significant competitive advantages, especially to early adopters. We believe it could both increase their revenue and help them recruit clients away from competitors. This important “WealthTech” effect makes it possible for prospective clients to be shown, in minutes, an answer to this key question: “How did my choices do in comparison with all of the others I could have selected?” When the answer reveals that the top scoring funds produced average returns hundreds of basis points higher per year over the last 5 years than theirs, for instance, often with less volatility (i.e., no equivalent risk premium for that large return premium), the “recruitment” of that client away from a competitor may be easy to envision. If that begins to occur, the adoption of this decision technology may accelerate and, with that growth, we believe a beneficial transformation of the financial services marketplace could result, with or without additional regulatory action.

(11) The decision-assistance technology was developed, tested, and practically applied within an SEC registered investment advisory firm for nearly a decade before it was transferred, to Decision Technologies Corporation to facilitate its further development and distribution – to make available within the brokerage and investment advisory communities.

(12) The fact that similar (though non-identical), overlapping rules by the SEC, DOL, and various states (e.g., NY, NJ, MD, NV, and likely others) are now being considered and adopted simply heightens the perceived need for a single process that can help to ensure compliance with them all.